For someone perhaps best known for spectacular failure – losing 6:0 to Bobby Fischer – Mark Taimanov has had the most successful of lives. A top Soviet grandmaster and a successful concert pianist, he’s now the happy octogenarian father of 6-year-old twins. He talks about his life and contemporary chess.

Mark Taimanov was born on 7 February, 1926. He took part in the formidable USSR Chess Championship a record 23 times, twice tying for first place. He lost the first play-off to Botvinnik in 1952, but then won in 1956 against Boris Spassky and Yury Averbakh (who turned 89 last week). Victor Korchnoi, a month away from becoming an octogenarian himself, finished that event half a point behind.

For his 85th birthday, Taimanov, still in sparkling form, gave a number of interviews, including the following:

Sport Weekend: “The best musician among chess players and the best chess player among musicians”, Vladimir Vashevnik

Rossijskaja Gazeta: “Life is a game”, Evgeny Tsinkler

Izvestia: “Playing black and white”, David Genkin

I’ve translated some of the highlights from those interviews below. Although the questions largely concentrated on Taimanov’s remarkable career, he also gives his opinion on the state of contemporary chess, and talks about rising stars like Magnus Carlsen and Hikaru Nakamura.

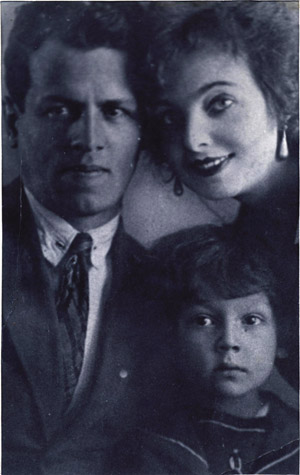

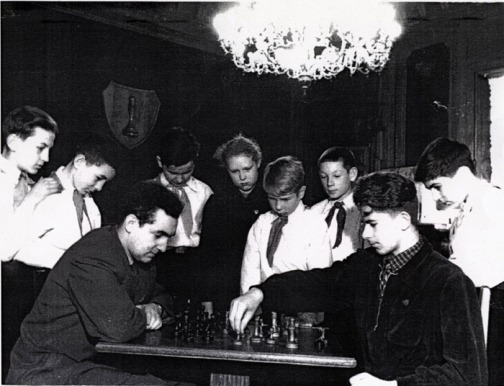

The photographs, unless stated, are taken from the remarkable selection Taimanov made from his family album to mark his 80th birthday:

e3e5: “My biography”, Mark Taimanov

Chess and music

Taimanov was introduced to music by his mother, who taught the piano at the conservatory in Kharkov, Ukraine, before the family moved to Leningrad. His first brush with stardom came early on:

And then you became famous for playing the role of the violinist in the film “Beethoven’s Concerto”. But how did an 11-year-old boy play a violinist in a film, despite being a pianist?

They gave me a teacher, who in a short space of time taught me not only how to hold the violin elegantly and correctly, but also to play some fragments of Beethoven’s concerto. I had to learn the fingering with my left hand on the fingerboard and bowing with my right. It seems I managed – even in close-ups you can’t see anything wrong.

Many many years later the wonderful American violinist Isaac Stern came to give concerts in Russia. We were on good terms and spent a lot of time together. He once shared his impressions with me after a master class in the conservatory: “You’ve got a lot of talented young violinists, but strangely they all have a very dull and inartistic way of holding the instrument. I’ve only once in my life seen a young Russian violinist who really held the violin elegantly. That was in the film “Beethoven’s Concerto”. “Isaac”, I said, “that wasn’t a violinist, that was me!”

And in 1937, when the Zhdanov Palace of Young Pioneers was opened I was among those invited for that event as the “film star” Mark Taimanov. The Director of the Palace asked me where I wanted to study. And an internal voice prompted me to reply – in the chess club. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

Taimanov is often very modest about his achievements in music, but at the very least he was a top pianist in the Soviet Union, and eventually achieved international recognition:

In its time your piano duet with your first wife, Lyubov Bruk, was very famous. But what do you consider your greatest achievement as a pianist to have been?

My highest honour in music was our duet being included in the “Great Pianists of the Twentieth Century” series produced by Philips and Steinway. Among the seventy albums, along with names I’ve always bowed down to – Rubinstein, Rachmaninov, Horowitz, Gilels – there’s a sole piano duet, Lyubov Bruk and Mark Taimanov. That was a total surprise and an incredible source of pride. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

It’s not hard to find music by Taimanov and Bruk on the internet. The following, for instance, is wonderful:

Of course as a chess player who was in or close to the world top-10 for over 20 years, Taimanov has often been asked how he managed to combine his two careers:

They joke that you’re the best musician among chess players and the best chess player among musicians. Like Philidor – you always have black and white in front of you – the piano keys and the pieces on a chessboard.

Having two professions meant I managed to avoid professional jealousy – musicians could consider me a chess player and chess players – a musician. I considered those I played against not opponents, but partners: together we created a work of art – the game of chess. It was the same as the way in which my first wife, Lyubov Bruk, and I would create works of music at the piano. (Sport Weekend)

He’s always rejected the suggestion that concentrating solely on chess might have seen him achieve even more than he did:

Mark Evgenyevich, written on your calling card there’s: “Mark Taimanov. Grandmaster, pianist”. So then, chess after all comes first?

Let’s say it’s alphabetical. I still haven’t determined what comes first for me. I don’t feel as though I’d have had great success if I’d devoted myself to just one thing. I think that with the opportunities I was given by nature and fate I achieved the maximum I could. Fortunately I’ve got a weak character, so I never did decide to dedicate myself to only one of my professions. And I’m very glad. After all, if I’d rejected chess or music then my life wouldn’t have been two times, but a hundred times less interesting. Firstly, music and chess – they’re a wonderful combination, as they say, for the mind and the heart. And secondly, the circle of my acquaintances was significantly increased precisely because I combined them. Besides, psychologically I always had something to fall back on. A man who suffers a serious failure in his only profession is unhappy. It’s something else entirely if you have another occupation which is just as important and which you love just as much. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

Famous encounters

No interview with Taimanov seems to pass without his recalling how he met some of the best-known figures of the twentieth century, including Winston Churchill, Nikita Khrushchev, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara:

My life included many meetings with people who feature in the encyclopaedias. The first World Student Championship was to be held in England in 1952. We were given the order to “ensure victory”. They chose Grandmaster David Bronstein and International Master Taimanov. True, David had never been to university, and I graduated from the conservatory, but we were the right age. We were summoned by Nikolai Mikhailov, the Secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee. The conversation was short: “You must finish in first place! Do you know who signed for your trip? Joseph Vissarionovich [Stalin]!” I almost fell off my chair. There was no alternative – only victory, and we shared 1st and 2nd place. In June 1954 we played against the English and visited parliament. Over tea I asked Sir Winston Churchill about his foibles. He answered that his favourite cognac was the Armenian “Dvin”, and his favourite cigars were “Romeo y Julieta”. Later in Havana I was introduced to the master who made Churchill’s cigars by hand. […]

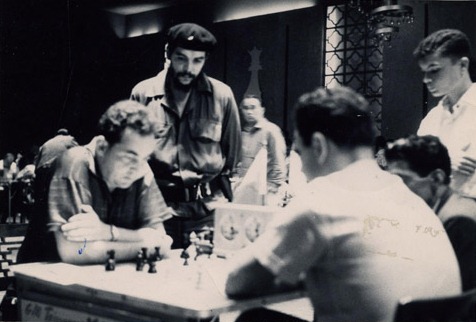

You also met Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara.

We became acquainted as a result of my participation in the Capablanca Memorial. Smyslov and I drew and were discussing our game. Che took an interest and came up to the table with his interpreter. He introduced himself modestly and then asked a few questions. His evaluation of particular moves showed that he played at the level of one of our candidate masters. When the tournament was over Che was invited into the embassy as an honoured guest. We managed to talk there. He said, bitterly: “I feel as though I’ve exhausted myself here… Politics, economics – that’s not my calling. I should be raising nations up in a struggle for freedom!” Before parting he signed his photograph: “To my friend Mark Taimanov. Che”. We met for the last time at the Capablanca Memorial in 1967. He passed away in October that year… Fidel didn’t play so well. I managed to talk to him on a few occasions. He took part in one of my simultaneous displays.

Dmitry Shostakovich loved chess. He told me a story from his life. At the beginning of the 1920s he made some extra money as a pianist in the “Barrikada” silent movie theatre. Once, during the intermission, he noticed a tall fair-haired man who was studying a position in the lobby. Mitya went up to the table and heard: “Young man, do you play chess? There’s still time before the performance starts”. “I wasn’t sure: I was a weak player,” said Shostakovich, “but curiosity won out and I accepted the invitation. My bad moves embarrassed my playing partner – he looked at me in amazement. The game finished logically with my getting mated. ‘Don’t be upset’, my playing partner said. ‘You lost to Alexander Alekhine.’” (Sport Weekend)

Taimanov also had no reason to complain about the chess players he encountered at the start of his career:

You had the good fortune to be a pupil of Botvinnik himself…

Well, not immediately, of course. It was only when I’d already had some success that Mikhail Moiseyevich took me into his group. He was an amazing teacher! He said: “I don’t have to teach you to play chess. I have to teach you to learn”. He never gave us lectures, but instead set us problems that concerned various aspects of chess: openings, endgames, middlegames. And then he would listen and take a critical interest in our thoughts. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

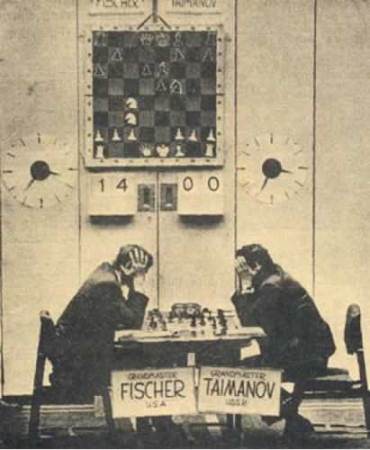

Whitewash against Bobby Fischer

Mark Taimanov is perhaps best known for losing 6:0 to Bobby Fischer in 1971. The American grandmaster then went on to beat Bent Larsen by the same scoreline, overcome Tigran Petrosian by a slightly more respectable 6.5 – 2.5, and then, of course, he clinched the World Championship by beating Boris Spassky.

It was also a turning point for Taimanov, who suffered repression from the Soviet authorities solely, it seems, on account of Soviet chess having suffered a serious loss of face:

After that encounter they took away my “Honoured Master of Sport of the USSR” title, banned me for some time from overseas trips and forbid me from being printed. The formal pretext for the punishment was supposed to be that the customs officers found a book by the then still Soviet writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn – “In the First Circle”. But, despite all that, I recall that encounter with Fischer with enormous pleasure. Yes, the sporting result was depressing, but I had no reason to be embarrassed by the content, the creative side of the games. […]

But more than that, I’m glad that fate in general allowed me to play a match against that great grandmaster. I was also one of the last to have the chance to meet Robert Fischer at the chess board.

In 1992 I wrote a book with the title “I was a victim of Fischer”. I sent the first copy to Robert. His reaction was immediate: Fischer expressed his gratitude and said that he liked the book. (Izvestia)

The score of the match was perhaps not a fair reflection of the play, though note Taimanov’s final comment here:

Returning to your legendary match against Fischer, do you nevertheless think that you had chances of winning?

No, I don’t think so, but I probably shouldn’t have lost by such a score. Fischer himself conceded that. He said the result didn’t correspond to the way the struggle went in the match, and that by the sixth game in his opinion the score should have been no more than 3.5 – 2.5 in his favour. But the psychological factor played a role. It was the first time I was encountering not a playing partner, but a computer that didn’t make mistakes. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

Bobby Fischer – oddball genius

Mark Taimanov knew Fischer since the latter was a teenager, and often talked about him. For example:

But what about Fischer? After all, for him nothing existed in the world except chess.

Yes, but perhaps that’s precisely why he was interesting. After all, he wasn’t simply a professional chess player, but a minister of that cult. I never even saw him without a chessboard.

Here’s an example. For a period of time he was fascinated (which happened extremely rarely with him) by a charming St. Petersburg woman called Polina. She didn’t speak English, however, and Fischer asked my wife, Nadya, to be an interpreter on their romantic date. Polina was running late. Fischer was dressed strangely: despite the summer heat wave he was wearing a leather coat, with all the buttons fastened, while he had a bag in his hands which, of course, contained a chess set. The first question he asked Nadya was: “Do you play chess?” And then, until Polina appeared, he couldn’t find another topic to talk about.

Chess was his life, his philosophy. He even said that the five years he spent in school were lost for him, as he could have devoted that time to chess. He probably was uneducated, but you couldn’t under any circumstances accuse him of a lack of erudition. His IQ was incredibly high.

At the same time Fischer had some abnormalities. For example, he hated communists and was a terrible anti-Semite, although his mother was a practising Jew. Yes, at certain moments he could be unpleasant and even insufferable. But he was a genius, which means he had the right to certain oddities, as after all genius is an abnormality in itself. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

Contemporary chess

As one of the last men alive to have been at the centre of the enormous popularity of chess in the Soviet Union, Mark Taimanov’s reflections on the current state of chess are of particular interest:

Alekhine, Tal, Botvinnik… In the past everyone knew the names of chess players. But, it seems, that ended with Kasparov. Why?

Yes, I’d say that with Kasparov, the thirteenth World Champion, the golden age of chess came to an end. The thing is that up until the thirteenth they were all vivid, original personalities. There’s the great Lasker – a philosopher and thinker. The brilliant Capablanca – Mozart at the chessboard, a diplomat, a handsome man and a polyglot. There’s Alekhine – a prominent lawyer and the most interesting of men, there’s Euwe – a professor, a strong mathematician. Each World Champion was also interesting beyond the chessboard. It was always an event to watch the clash between people who were such opposites in terms of temperament, interests and public views. Take, for example, the Karpov-Kasparov match. That wasn’t just a chess encounter, it was a struggle between two worlds!

If you look at today’s champions, however, then the majority of them don’t arouse any particular interest beyond chess. Well, maybe Vishwanathan Anand stands apart – perhaps because he’s Indian. Besides that he’s extremely intelligent by nature and doesn’t get involved in any toilet scandals. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

Another two aspects of contemporary chess that Taimanov regrets are commercialisation, and computers:

Have computers been a factor in the way the game’s changed?

Yes, they’ve been a negative influence. Chess has lost its analytical side. That function’s been taken over by the computer. You can get a position after 15 moves in the Najdorf Variation of the Sicilian Defence. I struggled with it for years, but the players don’t know what to do next. For some, independent play only starts on the 25th move, and ends two moves later – the computer considers the position drawn. The creative aspect has been strangled. Now it’s mainly a spectacle. They play at blitz speed. There’s no analysis of positions. You can watch the game at home, which is equivalent to listening to an opera on a recording instead of in the theatre. The media mainly covers scandals. For example, the toilet scandal during Kramnik’s match against Veselin Topalov. (Sport Weekend)

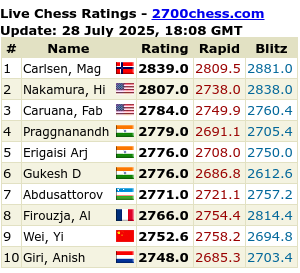

Although understandably focussed on the past, Taimanov also comments on some of the up-and-coming stars. For example, Carlsen:

Among the men the most talented representative of the “new wave” is the Norwegian Magnus Carlsen. Before turning 20 he managed to win a number of super-tournaments and occupy first place on the rating list. It’s a pity that he withdrew from the Candidates Matches. In that regard he’s copying Fischer. (Sport Weekend)

And Nakamura:

Let’s return to the tournament in Wijk-aan-Zee. Was it at a surprise for you that first place was taken by the American Grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura?

I’ve been following that chess player for a couple of years already. I’m impressed by the vitality, imagination and calculated risk in his games. I think the victory of the young American in Wijk-aan-Zee was a little unexpected, but fully deserved.

Some people already see him as the new Fischer…

I don’t think there’s any point rushing to such conclusions. Robert Fischer was a genius, and geniuses, as we know, can’t be cloned. Moreover, in terms of the way he plays, and his character, Nakamura isn’t like Fischer at all. (Izvestia)

Taimanov later returns to Wijk-aan-Zee in the same interview when talking about the loss of status suffered by chess:

We talked about the very strong tournament in Wijk-aan-Zee. But tell me, did even one social or political newspaper in our country cover it?! Or try going onto the street and asking passers-by who holds the chess crown at the moment. I’m sure the majority of people will just shrug their shoulders. But when Mikhail Botvinnik entered the theatre the audience would stand up and applaud.

Happy families

For an 85-year-old man, Taimanov has an unusual family situation.

Mark Evgenyevich, your life has been rich in amazing acquaintances. Can you pick out the most important encounter of them all?

Easily. That was in the hospital when I met my twins – Masha and Dima. When children appear in the world everything else really does appear trifling. And I must say to those who are about my age that I’ve never felt happier than I do now, when life is focussed on these wonderful creatures. Thank you, Nadya, for that!

The difference in age between your first son and the twins is 57 years – in essence, two generations!

Yes, we have a very funny situation. Misha and Dima end up being the aunt and uncle of my granddaughter. And she’s 27. (Rossijskaja Gazeta)

You can see Mark Taimanov with his family at the end of this short NTD news report from a book promotion earlier this year:

Here’s wishing Mark Taimanov a slightly belated 85th birthday!

Amazing photo of Nakamura at Tata Steel. An intense portrait of concentration.

Could you please create a “best of” or “golden treasury of” ChessInTranslation? A tag or a page?

It should have links to this page, and interviews of Spassky, Chucky etc. Maybe also the KID article….

Let it be at your discretion (possibly based on comments by idlers like me) as to which article deserves to go there.

Also the article by Odessky (during tal memorial, was it?)

Thank you for these interesting excerpts from

the life of a great artist!

> For an 85-year-old man, Taimanov has an usual family situation

unusual (I suppose)

Thanks, Marcus! I’ve corrected it.

Chandler – yes, I was planning on doing something like that. And I think we probably agree on the articles as well :)