After last year’s Tal Memorial, where Viswanathan Anand drew all nine games, he gave a long and fascinating interview to Vlad Tkachiev. Topics included the champion’s current form and the upcoming match against Boris Gelfand. On the eve of that match I’m resposting the interview here as it’s currently unavailable at WhyChess.

After last year’s Tal Memorial, where Viswanathan Anand drew all nine games, he gave a long and fascinating interview to Vlad Tkachiev. Topics included the champion’s current form and the upcoming match against Boris Gelfand. On the eve of that match I’m resposting the interview here as it’s currently unavailable at WhyChess.

The following interview, which I translated from Russian into English, first appeared at WhyChess on 23 December, 2011:

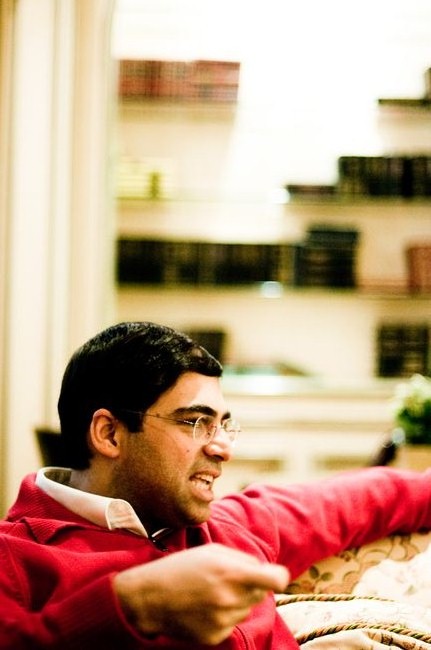

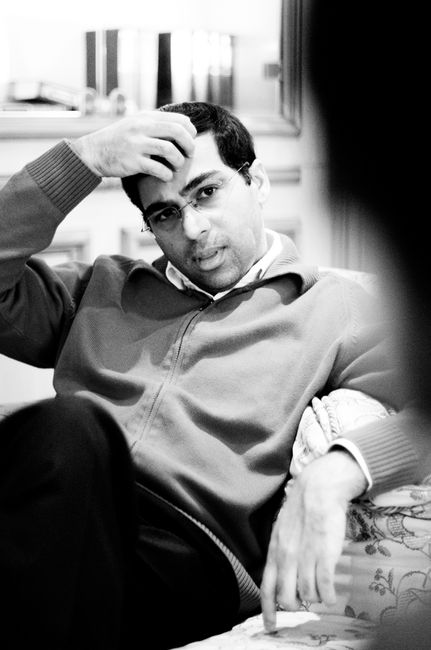

Vegetarian Predator

Viswanathan Anand

on World Championship matches, the new generation of top players and himself

Text: Vlad Tkachiev

Text: Vlad TkachievPhotos: Irina Stepaniuk

The winner of everything it’s possible to win, tenacious, blessed with instant reactions and relentless at finishing off his victims – Viswanathan Anand has of course earned his nickname, “the Tiger from Madras”. But not only through his results. There’s also his somewhat feline manner, the melodious tone of his voice and even a love of cashmere sweaters – all reminiscent of the world’s most popular predator. But nevertheless, there’s an impression that his hunting instincts seldom surface nowadays, and even his always watchful gaze betrays concern.

Perhaps before he next pounces.

Vladislav Tkachiev: Vishy, what can you say about your result at the Tal Memorial?

Viswanathan Anand: In the final analysis 9 draws is still better than 6 draws and 3 losses. I feel as though I was lacking ideas and something else as well at the tournament.

Kramnik noted in an interview with me that it seems as though you lack motivation for tournaments, and your sharp preparation is mainly aimed at matches. Do you agree?

– The facts speak for themselves, but you can’t say I prefer matches and focus less on tournaments. The impression is that I lack some spark in tournaments. The question is whether it’s happening according to my wishes, or not really. I’d say it’s unconscious.

You’d like things to be different, but this is the way it goes.

– Of course it’s not something I want. The last two tournaments went particularly badly. Last year I didn’t win a single tournament, but at least I was second everywhere: in Bilbao, Nanjing and London.

Yes, but you’re not someone who can be content with second place…

– True. But it’s better than 6th. And even that’s better than 5th out of 6 players, or 6th out of 10.

After all, your name’s Viswanathan Anand.

– Yes, but the thing is that last year I wasn’t too happy either. And in Wijk aan Zee I was again second with +4. Something really is missing. It’s perfectly clear to me that Aronian and Carlsen are forging ahead, and Magnus by a little bit more than Levon. I’m not trying to justify myself, but it doesn’t only depend on me. Look at the first four prize winners at the Tal Memorial: Magnus, Levon, Ian and Sergey – the youngest participants in the tournament. Only Nakamura wasn’t among them. Ok, I can accept the fact that I didn’t really shine with the white pieces – it was the same for everyone, after all, as White scored -2. It’s easier for me to recall people winning with Black here. So… There are certain trends, and I can’t say I’m too proud of them.

Maybe you’re hiding something and keeping it in reserve for the match?

– No. If that was the case then after all I had no reason to hide anything last year.

Really?

– Yes. But I still didn’t win any tournaments. So there must be another reason.

Do you encounter any particular problems when you come up against the new generation?

– Well, my history with Aronian is well-known and, overall, it’s becoming harder and harder with such a quantity of computer opening preparation.

Did chess alter significantly with the appearance of the Berlin Wall? I’ve got the impression that many people have switched to 1.d4 not even because of the Petroff, but precisely for that reason.

– Yes, it really is impressive. I imagine Vlady sitting in his flat 12 years ago and deciding: “Why don’t I work out some openings for the next 12 years”. And he did. It seems as though even back then he was playing the Makogonov-Tartakower-Bondarevsky variation and the Berlin. And just take a look at the openings now – only those two! His work on the opening stage of the game is simply stunning.

I don’t know exactly how many lines he’s established, but you get the impression that for the last 10 years we’ve only been using his ideas.

I don’t think it goes that far, although he introduced a great deal.

– His stamp on opening theory is much more significant than mine. The Petroff, the Berlin… So it was fantastic luck for me to have him as an assistant during the match against Topalov.

But at the same time, you yourself completely outplayed Vladimir in that aspect, winning your match even before it began i.e. you essentially did to him what he did to Kasparov. You made him play sharp forced variations from the very first moves, which isn’t something he particularly likes.

– Perhaps. Vlady and I have probably played over 150 games, if you include rapid.

And what’s the overall score at the moment?

– That’s the thing – it’s practically even.

Well, you’ve probably dominated in rapid?

– I had +5 or something like that before Bonn.

And in turn he was leading in classical.

– In classical he had +2. In any case, the word “dominated” would be too strong, as it was almost even.

And if after that you win a match with a gap of 2 or 3 points, then it means something’s happened. I think it was simply that all of his preparation went down the drain. I managed to dictate… In a certain sense I beat him the way he beat Garry.

That’s what I was talking about.

– Garry didn’t take part in London, and Vlady didn’t in Bonn. It was something like that. And he was right when he said that if his preparation had succeeded he’d have looked like a completely different player.

I’m sure that success owed a huge amount to your seconds: Kasimdzhanov, Nielsen.

– Undoubtedly the team means a lot. During the match it’s very hard to say who did what exactly, but my team was unquestionably a good one. And the match strategy also turned out to be correct.

To force him to play sharp lines?

– Let’s say my main goal was to avoid ending up in the position of that guy from the London match, if you see what I mean.

To avoid playable endgames which are almost drawn, but…

– It’s not only a matter of endgames. I simply tried to avoid positions against Vlady in which you suddenly feel completely powerless, and you look around in vain for any help. For me London was one of the most impressive matches, and back then Vladimir managed to completely disarm Garry. He can do that sometimes. Occasionally you play against him and get the feeling that you could play ten games without a single one of your pieces making it beyond the 4th rank. Well, or something like that. Garry looked extremely helpless and there’s no-one else but Kramnik who could pull off a thing like that. It was clear that was where the main danger lay. But I couldn’t have imagined that everything would go so well.

It went beautifully: we’d prepared an idea and it occurred in the 3rd game, and then in the 5th everything went well again, despite the risk. Then in the 6th our brilliant work again bore fruit. But having 3 ideas come off in only 6 games – that was of course something I didn’t expect.

Do you think, Vishy, that if another match took place between you and Kramnik you’d be able to repeat that success?

– It’s always a possibility, but it would be very tough, because there’s no doubt Vlady also learned a lot on that occasion. After all, you can prepare for a match for a year, or three – the only thing that matters is how much more confidence it gives you.

Do you share the common view that you’re a clear favourite against Boris Gelfand?

– I never think in such categories, as I don’t know what the term “clear favourite” means.

Have you already started to prepare?

– Not too seriously, although of course we’ve already started to think about Boris and all that. It goes without saying that after London I’ll start preparing more intensively.

Vladimir told me what impresses him most is how you play with knights. Could you describe Gelfand’s style? After all, you started your careers at almost the same time and you’ve played so many games…

– Well, his games usually feature logical development. What I mean is that you know what your goal is, and that’s why you play in such a way, and in the end you get a logical construction. Plus, of course, Boris has had a very good chess education.

With all the drawbacks and benefits of being educated like that?

– Yes, if you like. He’s definitely got a consistent approach to the game. What can I say… of course, he’s a very, very classical chess player.

Who was your most difficult opponent? Kasparov?

– Yes.

Because of the psychological pressure he applied?

– Most of the time it was Kasparov, but sometimes Topalov.

But it’s no longer Topalov?

– It changes all the time, and I haven’t even played him since Nanjing. But for me it was mainly Kasparov.

What was the main reason?

– Well, I think my mistake was that I turned up for the 1995 match as if it was an exam – here’s my preparation, and I’ll follow it whatever happens.

And he performed the role of a professor.

– No, not a professor, but my approach was that of a schoolboy, not particularly sophisticated.

It’s very hard to prepare for that in home conditions, even if your seconds frighten you with what’s in store. You can only learn from your own experience. I’d say I was naive in that match – I simply thought I had to be prepared, find good moves, make them and that was all. But, of course, matches… A match is much more. That’s actually why it was that we drew 8 games, then I won one but suddenly went on to lose almost all the remaining games that week. And I can’t explain it. It seemed as though I suddenly fell to pieces, and because of that I had difficulty for years afterwards playing against Garry. But there’ve also been other sources of unpleasantness: Levon, for example, has a good score against me, there were a few tough years against Vlady, Topy…

And is it true that after playing a super-novelty in the 10th game Garry began to deliberately slam the door?

– Yes, of course.

And it was done on purpose?

– Yes, I think so. That was also a mistake of mine, that I didn’t simply go up to the arbiter and say, “Could you make him stop doing it?”, or something like that.

How often did he do it?

– Maybe 3 or 4 times. What I mean is that he’d come up to the board, make a move, walk away and slam the door behind him. I’m pretty sure he did it consciously – he really wanted to take revenge for the previous day. Here we’re again getting back to the London match. While in the 10th game I again played the Open Ruy Lopez, as if to say, “Show me!”, Vlady kept dodging and deviating, playing the Archangel Variation immediately after the 2nd win. I could also have played the Scandinavian Defence in Game 10, as I’d prepared it for one game. My friend Hans Walter Schmitt would have been happy as he’s played it all his life. Perhaps I’d still have lost, but at the end of the day you have to show some… But I acted like a naive schoolboy. I definitely should have lodged a protest with the arbiter. Karpov would have done it without thinking, and we all know what a tough customer he is.

I remember the thought running through my head: “Should I say something?” And I thought that if I did I’d look stupid, as after all my position was lost in any case. But that’s not the point. You simply have to fight. That was my mistake.

After so many victories how do you manage to find the motivation again and again? Maybe your wife plays a big role in that, or is it something strictly internal?

– It’s almost always automatic for me. I think it’s a normal desire to strive to win a tournament you’re playing in. It’s not about it featuring in some sort of list: “Ok, I’ve already won Linares once, so I can cross that off. It’s been done.” Where does the desire to keep playing come from? I think it largely happens automatically, and the pleasure should also be natural. It’s very hard to force or control that. You can create ideal conditions, but it happens by itself. Too much passion can also interfere with your play – again, it becomes too hard to control.

I remember once playing alongside you on the Cannes team. Back then I was shocked by your interest in the Bacrot – Godena game, which had no theoretical significance: you analysed it for a few hours in the hotel room, and then for just as long with other members of the team. I literally couldn’t believe my eyes…

– Yes, I remember that game and the subsequent analysis very well.

And it becomes clear that the position is much more complex than you thought; and you can’t get it out of your head.

You return to your room and even with the computer you by no means immediately get to the bottom of it. It’s a very good thing when a chess player can maintain that curiosity.

More often than not, after all, there’s no question, sorry, there’s no answer.

– No, it was right the first time – more often than not there isn’t a question and that’s the problem. And when there isn’t one you don’t search. The most beautiful thing in chess is posing such questions.

You don’t have any objections to the fact that your match against Gelfand is taking place in Russia?

– Of course not.

Even given the fact that he’s considered almost a local player, while you aren’t?

– Sure, it would be great to play in India, in my home town. I remember all my school friends asking me: “It seems the Indian bid won?” They didn’t know the details as it had been announced that India was getting the match. Of course that would have been very good, but the Moscow bid also suits me. I’ve played here very many times, and always with pleasure.

Why haven’t you played for the Indian team lately? After all, you’re a national hero…

– Well, after Turin… What I mean is that I didn’t like things there at all.

Why?

– Above all, the atmosphere at the event was very bad. After that I lost interest in the Olympiads for a while. We’ll see, perhaps… Besides, some of the regulations are getting stranger and stranger, for example, the ban on being late.

That seems absolutely unnecessary.

What are your interests besides chess? Could you describe one day in the life of Viswanathan Anand?

– It depends what my schedule is for the following days.

An ordinary routine day.

– If I’m totally free then… I suppose just normal things: I might watch a film, listen to music.

Which film genres do you prefer?

– I don’t have any particular genres or types of film that stand out, or in any case I don’t see a pattern. I like some while I don’t like others at all.

But still, do you prefer art house, or have you got nothing against average blockbusters?

– It’s all mixed up – I’ve watched profound films that are expressive and enthralling, but also all kinds of trash. Sometimes you go to see a film like all the rest, and then you can’t understand why they do it.

I also love reading scientific literature and books on astronomy. It’s simply incredible how much information you can find nowadays on the internet on almost any scientific topic.

I read a lot about mathematics, physics and similar topics. Fairly popular stuff, in which very, very complex things are explained intelligibly. Recently I’ve taken a liking to books on neurology.

NLP? Neuro-linguistic programming?

– No, not programming. Works which describe how the brain works and look into experiments connected to that. I mainly read them in order to distract myself and get away from chess. To let my brain stretch its legs, so to speak.

Does it work?

– Yes, very well even. Actually, when I’m not thinking about chess I don’t think about it at all.

What about music?

– I mainly listen to the music of the 80s.

Disco, rock or…

– Rock: U2, the Pet Shop Boys… I like the lighter variety. And now, of course, Green Day, Coldplay…

Nothing connected to counterculture, but instead the mainstream?

– Yes, exactly. I’ve never been drawn to counterculture, Nirvana, for example. I remember maybe one song. Probably I am who I am. When you look at me it’s unlikely you think about counterculture.

How do you get rid of the stress after, for instance, a tense five-hour game?

– Usually I go to the gym. There you sweat a bit and get pretty tired and after that you can get ready to sleep. I can also watch a film or a TV-series on my notebook.

But not everywhere has fitness facilities.

– Then long walks, as in Wijk aan Zee, for example. That lasts about an hour for me there. Bilbao’s also very good in that regard, and Monaco. The main thing is to try and switch off.

Are you still a vegetarian?

– Yes, as before, I don’t eat a lot of meat. To be precise, I avoid red meat – beef, pork and so on. But I’ve been eating fish for a long time. So I’m not entirely a vegetarian, per se.

What’s your favourite cuisine?

– Oh, lots of things. I like Latin American food: Mexican, Chilean, Peruvian.

Brazilian’s incredibly good. Asian: Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Thai, Indian – the usual set. Middle Eastern, Italian and Mediterranean as a whole.

What about Russian?

– I really like borsch. It’s a pity it’s usually cooked with meat. Fortunately when I visit anyone the people who know me cook it in a vegetarian manner. When I come to Moscow I also often go to Georgian restaurants.

Ah yes, my favourite food is Georgian and Uzbek.

– Uzbek cuisine is also wonderful.

But again, Russian cuisine can be tricky for me because of all my restrictions. I like pancakes and all those things with mushrooms inside. In general, when I talk about Russian cuisine I’ve mainly got snacks in mind.

Nowadays it’s not uncommon to observe you spending more time on a game than your opponent. Previously it was hard to imagine such a thing was even possible. You don’t have the old confidence?

– Perhaps, but life simply teaches you to be more cautious when you recall too many incidents connected to playing too quickly.

But in your case you’ve got far more pleasant memories!

– It’s true that even now I can have good games when I play quickly. Often my intuition doesn’t let me down, but if I start to think then it all becomes a mess. So very often I’m glad to maintain a fast tempo.

About 20 years ago Dreev, after losing a match, said that your ultra-fast play at the time was connected to some kind of Indian national game, in which you had seconds to respond to questions.

– No, but when I was young I’d very often play blitz in the chess club – that’s probably where the habit came from. But I’m convinced that the way you play reflects your personality. I also take a lot of decisions in life without delay, as I don’t really like having too many doubts.

Do you agree with the general opinion that you’re one of the most talented players in the whole history of chess?

– I think you have to ask such things of people who aren’t involved. It’s very hard for me to compare myself to others, particularly to those I’ve never met. So I haven’t got a clue. I’m simply not capable of looking at myself so objectively.

When 20 years ago you’d spend 15-20 minutes on a whole game against the world’s best players was that a consequence of enormous confidence, excess energy or something else?

– No, but… If I was sure that the move I was planning was good then I’d make it rapidly. It was a kind of curiosity –

You wanted to provoke him into the same rhythm?

– Yes, exactly. I think that’s how it was. My main problem isn’t excess confidence, but…

Its absence?

– I’m more often lacking in confidence than too confident, let’s say.

How long are you going to remain World Champion? Honestly.

– Frankly speaking, as long as they let me. I don’t have an answer to that question. I’ll try to extend my term as Champion as long as possible.

Do you see a clear challenger on the horizon?

– Boris is now a very dangerous opponent. Simply because… he’s a very experienced, extremely hard working and motivated player. I can’t think beyond that as what would be the point? First let’s see what happens and if I win then it’ll be possible to worry about what’s next.

Of course, everyone sees that at some point Aronian, Carlsen, perhaps even Sergey Karjakin will appear, but…

Excellent. We’ve already talked about Gelfand, so now about the latest generation. Could you outline their strong points? Why, for example, have things gone so badly for you in your black games against Aronian?

– Actually I lose to him more often with White.

I didn’t know.

– Ok. Magnus has an incredible innate sense.

What do you mean?

– The majority of ideas occur to him absolutely naturally. He’s also very flexible, he knows all the structures and he can play almost any position. Aronian’s inferior to him in terms of breadth. For example, Magnus plays both 1.d4 and 1.e4, while Levon never plays 1.e4. The main thing is that I think Aronian’s a much more tactical player than Carlsen. He’s always looking for various little tricks to solve technical tasks.

Do you think Carlsen’s a new Karpov, as he was in the 70s and early 80s?

– I don’t know Karpov that well. I think Carlsen’s much more universal. There haven’t been many such players at all, perhaps Spassky in his best years.

Ivanchuk’s the same, but it seems to demand much more effort and thought from him.

Why did Magnus decline to take part in this World Championship cycle?

– I haven’t got the slightest idea.

Kasparov’s influence, a protest against the qualifying system, or was it something else?

– Perhaps. It’s something I’ve never tried to understand. He didn’t play – well, so he didn’t play.

Re the interview ‘translated from Russian into English’, Anand gives interviews in Russian?

I think the interview must have taken place in English, but it was edited and published in Russian. And then I translated it into English for WhyChess. So it’s a bit like a game of Chinese whispers, but hopefully too much wasn’t lost in the process!

great interview!