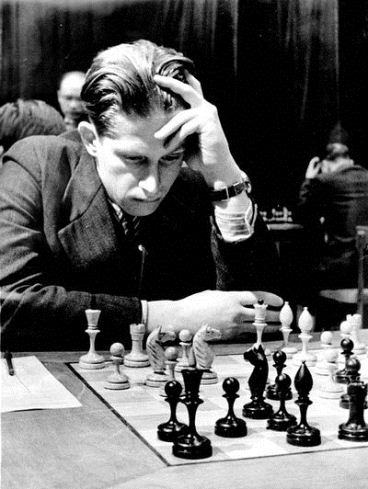

Yuri Averbakh, the world’s oldest grandmaster, celebrated his 90th birthday on February 8th this year. To mark the occasion he gave a long and fascinating interview to Vladimir Barsky and Eteri Kublashvili, which turned into a whirlwind tour of chess history.

Yuri Averbakh, the world’s oldest grandmaster, celebrated his 90th birthday on February 8th this year. To mark the occasion he gave a long and fascinating interview to Vladimir Barsky and Eteri Kublashvili, which turned into a whirlwind tour of chess history.

Averbakh was born in Russia in 1922. As a boy he saw Emanuel Lasker play, and he went on to be an eyewitness to almost the entire rise and fall of the famed Soviet School of Chess. Although overshadowed by some of his better-known contemporaries he was a talented player who won the formidable USSR Championship in 1954 and tied for first place with Mark Taimanov and Boris Spassky two years later (Taimanov won the playoff). A noted chess journalist, author and arbiter, he’s now focussed on the history of chess and other board games, where the range of his erudition is dazzling. The new interview includes fascinating examples stretching back 25 centuries and encompassing countries all around the globe.

What follows is a full translation of the Russian original at the Russian Chess Federation website. The photos of Averbakh are taken from the interview, as well as from the same site’s report on Averbakh’s 90th birthday celebrations.

Yuri Lvovich! First of all, we’d like to wish you a Happy Birthday!

Thank you.

It would be interesting to find out what you’ve been doing and what you’ve been taking an interest in.

At the moment I’m mainly studying the history of chess. Actually, it’s more than that – the history of the intellectual games that existed before chess. Do you know the simple children’s game “noughts and crosses”?

Yes, of course.

But did you know it was already described by Ovid in Ancient Rome? He has a work entitled The Art of Love. There he writes that it’s essential to be able to play “noughts and crosses”.

But what’s that got to do with the art of love? Crosses are boys, noughts are girls?

Well, it’s about how to deal with a woman, that you need to play with her…

The crosses always win, in contrast to how things work in real life…

No, if you play correctly you get a draw. So it’s a very ancient game. I suspect the Greeks had it as well, and Plato claims that all the games known to the Ancient Greeks (that’s the fifth century BC) were taken from the Egyptians.

And the Egyptians are actually from outer space?

Hardly. The games arose out of necessity. I can tell you about a visit I once made to Nepal. Funnily enough, I ended up there by mistake: the Nepalese wanted to invite the Deputy Chairman of the Sports Committee, but someone mixed things up and invited the Deputy Chairman of the Chess Federation. While I was there I managed to get to know the King of Nepal – he arrived by helicopter and landed right in a stadium. They warned me at the time that locals were obliged to kiss his hand, but they said that as a foreigner if the king stretched out his hand to me I should shake it and not kiss it!

In Nepal chess is known as “wise move” – “buddhichal”: “baddha” or “buddhi” means “wise” and “chal” is move. As well as chess they also have their own national game which is known as baghchal, or “leap of the tiger”. They hold regular baghchal championships in Nepal. The game’s played by two people on a square board, and there are two kinds of pieces: on the one hand – 20 goats, while on the other – 4 tigers. The tigers can of course take the goats, while the goats only have the right to push or crowd out the tigers. Obviously that game reflects the real situations goatherders would encounter when their herds were attacked by tigers.

I actually gave a lecture on the topic of “Games and Real-Life Events”. I’ll give another example. In 1732 Carl Linnaeus made a trip, while still a student, to Lapland. That’s in the far north of Scandinavia, where Sweden, Finland, Norway and Karelia meet. It turned out that the Laplanders play an original game: in the centre of a square board which is 7 by 7, 9 by 9 or 11 by 11 (the number of squares must be odd so there’s a central square) stands the King of Sweden. Around him are 6 fair-haired Swedes, while on the edges of the board are the enemies, the Muscovites. What’s that about? Not long before that, in 1709, the Battle of Poltava took place. So it was a faithful reproduction of Poltava, after which the Swedish King had to flee to Turkey. He stayed there for 14 years, by the way.

Recently I gave a lecture in Germany where I talked about the discovery I made that a long time before the Laplanders a similar game was invented by the Britons, the Celtic tribes that lived in Britain. That occurred in the 5-6th century AD, when the isles were invaded by the Anglo-Saxons.

So such “chess-like” games, if I can put it like that, arose in different locations around the globe?

Yes. The Romans brought their games with them to Britain and the locals borrowed them and then passed them on to the Laplanders.

So it turns out that modern chess is a synthesis of many similar games?

Yes.

Or do the “Indian roots” nevertheless dominate?

There are various theories, and none of them has been fully proven. There’s a lot of speculation, of course. However, given that the game includes representations of elephants and chariots, which were features of the four-part Indian army (elephants, chariots, cavalry and infantry), it’s still probable that chess was born in India. [The Russian word for the chess bishop also means “elephant”, hence the Chess in Translation logo! – CiT] The Indians are absolutely convinced about it, although they have no direct evidence; not a single historian has fully managed to resolve that problem – there’s not enough data.

But you’re inclined to believe that theory?

Yes. There are people who think chess came from China, but the Chinese have different rules, and the main thing is that originally Chinese chess wasn’t a game. It was instead used to predict the outcome of battles, and a magnet was used as well as the pieces.

In general, the history of chess is interesting because it’s very closely interwoven with the history of humanity and the history of the development of human thought. In Iran I heard a saying that’s attributed to Ardashir I, the founder of the Sassanid Dynasty (the heyday of Ancient Iran): “I don’t understand a sultan who’s incapable of playing chess. How can he rule his kingdom?” And it really is true that in Iran chess was used to train young princes.

And do you know what the treasury was called in England until the 19th century?

No.

The Chamber of the Chessboard! [The English term Averbakh refers to, and which I use from here onwards, is the Exchequer, which is actually still in common use today. For instance, the UK government’s finances are the responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The etymology is from chess. “Shah” was Persian for king, “shah mat” was “the king is dead”, or now “check mate”. “Checked/chequered” began to describe not just the chessboard but the general pattern – CiT] William the Conqueror introduced a harsh system of taxes and created a special chamber for collecting taxes. The table on which the taxes were counted for wood, water and so on was covered by a black cloth divided into squares, which recalled a chessboard.

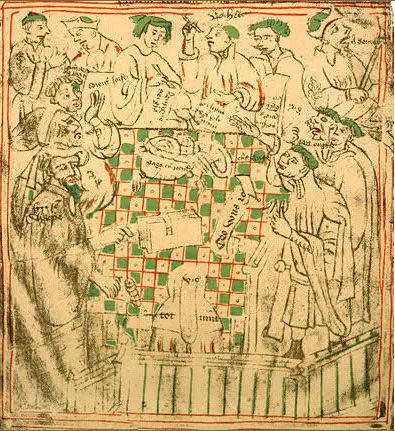

An Exchequer of Ireland was established in 1210, and is shown in this 15th-century illustration

The members of the chamber (they received the noble title of Barons of the Exchequer and had the right to include the board in their coat of arms) were known for their incorruptibility, and the taxes were probably gathered better than they are in Russia today. So the chessboard in the coat of arms was a symbol of integrity, while the process of collecting taxes itself was perceived as a battle between the treasury and the tax-payers.

And the treasury always won?

No, it varied… Another interesting fact: at the end of the 13th century the Italian monk Jacobus de Cessolis gave sermons where he compared the state to chess. He said: “In life, as on the chessboard, each piece has its own rights, but also obligations”.

Cessolis compared rooks with provincial governors, while he saw the pawns as the third estate, which included peasants, doctors and many more people, all the way down to crooks and gamblers. He considered chess to have been invented during the rule of the biblical tyrant Evil-Merodach, the son of the legendary Nebuchadnezzar: “While he was mowing down sages in Babylon left, right and centre and confusion reigned, the local nobility turned to the philosopher Xerxes with a request that he invent something to save the lives of the sages and princes and persuade the king to save the kingdom and rule it justly”. As you’ve no doubt guessed, the philosopher invented chess, and it calmed the tyrant’s temper.

So the educational significance of chess has long been known?

Yes, of course. In general, thinking people down the ages have, as a rule, been fond of chess. Napoleon loved it as well although he played very badly. Why? He was used to commanding hundreds of thousands of people and deciding the fate of whole countries – what were those small pieces to him? Of course he didn’t study chess, but it won’t just share its secrets with you without that! So Napoleon played badly, but he enjoyed the game and played it until the end of his life.

So it’s a paradox: Napoleon loved chess, but chess didn’t love him?

Yes, the title of my article on Napoleon was “Unrequited Love”. But did you know that Nicholas II was also fond of chess? In the chess museum in the Central Chess Club there’s a photograph of him playing. His cousins – the King of England and the German Chancellor – also loved chess. So what was the First World War? Three cousins organised a massacre in which ten million people died. There’s a “chess battle” for you…

Yuri Lvovich! It seems as though some unseen hand has guided you through life: you’ve probably visited every country with some relevance for chess?

Yes, that’s absolutely true! I’ve been to India three times, and I’ve been to a lot of other places as well.

But which country did you like most of all?

Italy. But I ended up there relatively late after I’d already travelled around half the globe – largely due to my knowledge of English. But do you know how I learned it?

When I finished school and enrolled in the Bauman Institute the question arose of which language to study. Our class consisted of 27 people and the overwhelming majority of them chose German (which I’d also studied in school, by the way). But I decided to go for English. It turned out there were only three of us for one teacher, and thanks to that we managed to learn the language quite well.

I was studying at the Thermal and Hydraulic Machinery Faculty in the Internal Combustion Engine Department. I studied engines and my thesis was on the Junkers diesel aircraft engine. If jet engines hadn’t been invented we’d still be flying diesel-engine planes, as diesel is cheaper and more economical. By the way, diesel engines have recently started to be installed in many luxury cars.

Anyway, it was even proposed that I could defend my thesis in English, but I decided there was no point showing off, as after all no-one would understand a thing.

Then I started working in a secret institute, where the administrative posts were occupied by generals and the director was the outstanding scientist Mstislav Keldysh. It turned out that knowing a language meant a 10% pay increase. My friend and I studied a little, took a paid exam and started to receive the increase. My work consisted of looking through English journals and selecting material which might be useful for us. As a result I very quickly began to earn 2500 roubles a month. When I switched to become a chess professional I was paid 1200 as an international master. It was only when I became a grandmaster that I started to get 2000 roubles.

On the other hand, it probably meant you had quite a lot of free time?

Yes, a whole new life had begun! After the thaw chess players started to travel abroad more often and unexpectedly it turned out that I had almost no competition. Previously it was obligatory for a head of delegation to travel with us along with a “plain-clothes art critic” [a KGB officer – CiT], who would often also be the interpreter. After the thaw the “art critics” ceased to travel. And among grandmasters themselves only three people knew a foreign language – Keres, Kotov and me. So if, for instance, the chess federation received an invitation from somewhere in the Far East the question would arise: who should they send? Keres felt he would earn more in Europe, and Kotov thought the same. But I liked travelling and would willingly go even to “exotic” countries. That’s how I visited India, New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and lots of other places. So fate decreed!

But why did you like Italy in particular?

Because in Italy you can take a single step, and it’s a step across a thousand years. You move from Ancient Rome to Papal Rome, i.e. ten centuries all at once. In Italy you can enter some shabby little village and suddenly see a wonderful old cathedral with paintings and sculptures by the great artists of the Renaissance. That’s what makes Italy interesting.

Did you find any interesting documents there connected to Gioachino Greco and Stamma?

When I was working on Calabrese, or Greco, I was curious how a young man with no education, with a social position only slightly above a servant, could spend time with the cardinals in Rome and travel all around the world? He first set off for Nancy, to the Duke of Lorraine, then with a letter of recommendation from that Duke – to Paris, and from there – to London and then back to Paris, and then in the retinue of the future wife of Philip IV of Spain he travelled to Spain. From Spain he set off for South America, where he died at the age of around 30. I had the suspicion that Greco was an agent for the Jesuits. They had a rule that if one of their agents dies he leaves all his property to the Jesuits. Greco did precisely that – he bequeathed everything to the Jesuits. And I asked some Italian acquaintances: “Could you have a look in the Vatican archives and see if there’s any material there connected to Greco?” So far they haven’t been able to find anything, but they discovered a curious document which makes it possible to determine quite accurately when modern chess emerged.

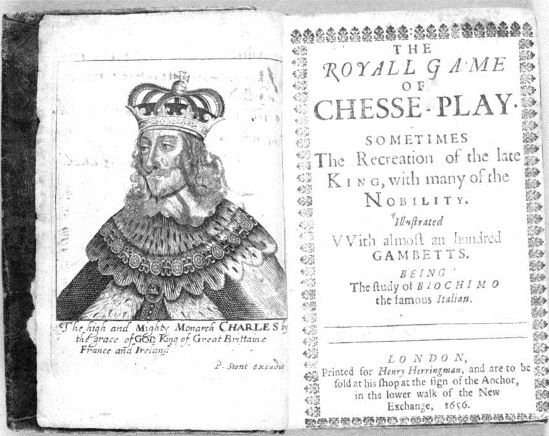

The 1656 London edition of Greco's manual

In general, it’s thought that the modern rules were finally established in the 18th century, or even in the 19th century, because the Italians long preferred the so-called “free castling”. Now, however, we know when the bishop and queen became powerful pieces, because in shatranj they were weak. That happened in around 1470 – which was when the first book on modern chess was published.

It was written by a Spaniard named Francesc Vicent. The Spaniards called chess “de la dama”, or “the game of the lady”. But which lady? It’s been suggested that it might have been Joan of Arc. No, it couldn’t have been, as she wasn’t called a lady but a maid, as she was only a girl. It turns out that chess was named in honour of Isabella of Castile, the queen during whose reign Spain was unified and all the Muslim emirates were abolished. Moreover, Pope Alexander VI was a Spaniard, and his daughter Lucrezia Borgia had a chess teacher by the name of Francesco. There’s a real suspicion that it was that same Francesco who wrote the first book on modern chess. The second was written by Lucena, and the third by Damiano, from Portugal.

Vicent’s book was preserved in the Santa Maria de Montserrat Monastery (located in the Pyrenees, on the border between France and Spain); incidentally, I’ve been there. But either during the Napoleonic Wars, or later still when there was a fire in the library, the book was lost. It seems, however, that it’s recently been found; a book’s been published in Spain with the title “Vicent Returned”.

It’s interesting that according to those same rules the queen and king were of equal significance, and the loss of the queen was equivalent to the loss of the king. In 1996 Kasparov visited Spain for a live chess exhibition, where they staged a game described in one of the ancient books. During the exhibition Garry showed a simple combination: the bishop takes on f7 with check, then knight to e5 check, and the knight takes the bishop on g4. But the thing is that the move knight to e5 was impossible back then as the queen on d1 would have been en prise… It was only later that people reached the conclusion that the queen could be exchanged and even sacrificed. Those are the sort of unexpected details you discover.

And besides working on the archives what else do you like to do? Do you watch any TV programmes or films?

Not always, you know. In general I like to watch discussions, although sometimes they make an awful impression on me. Here’s what I’d say: in Russia people aren’t capable of discussing, unfortunately. They’re not capable! They all start speaking at the same time, interrupting each other. If one person is speaking then everyone else should be silent. Zhirinovsky, for example, doesn’t let anyone else get a word in edgewise. It’s just impolite!

At the moment the media is talking a great deal about meetings: on Bolotnaya Square, Sakharov Avenue… [Where rallies have been held protesting against the alleged falsification of the recent Russian elections – CiT] What’s your opinion on that?

Positive. I think you have to allow people to express themselves. The policy of establishing a strict hierarchy of government, which has been in place for the last 12 years, hasn’t done any good. It’s become something like an inversion of Soviet power.

During Soviet rule – you said in one of your interviews – there was a slogan: “chess is a political weapon”. What did that mean?

I’ll give you a simple example. In 1923, when the Chess Union was created, there were 3000 qualified chess players. Ten years later we had 500,000 chess players. Does that tell you something? Unquestionably.

Chess appeared in my home when I was three years old, so in 1925. That was obviously related to the Moscow International Tournament. I learned to play chess when I was seven, and was still interested in it when the Second Moscow Tournament took place in 1935.

Did you go to the tournament?

No, but in our class we held a Category 5 tournament, and I gained that qualification. I was very proud of myself and brought home the certificate, but my dad just looked at it, threw it down and said: “If only you were more disciplined”. I had problems with that… So my father only took me for a chess player when I became USSR Champion.

But why didn’t you go to the tournament in 1935? Did you really not want to take a look at Lasker and Capablanca? Or was it difficult to get in?

You have to understand that I wasn’t yet so fascinated by chess. But nevertheless, I did end up seeing Lasker. At the time I was living on Bolshoi Afanasievsky Lane off Arbat Street, while on Starokonyushensky Street next to the Austrian Embassy was the Komsomolets Building. Simultaneous displays were organised there for Lasker and Spielmann, and I went to watch how the champion of our school, Alik Prorvich (he later worked for Soviet Sport), got on against them. The first person I saw there was Isaac Linder, who arrived in a red shirt. Isaac recalls that although Lasker beat him, he was full of praise for him. So that was the first time I saw Lasker.

77 years later Isaac Linder (92), also still an active chess historian, helped celebrate Averbakh's 90th birthday

But the person who made the greatest impression on me was Nikolai Dmitrievich Grigoriev. Back then I was looking for a place I could play chess, and went to the Ministry of Justice Club, which was located on the corner of Ilinka Street and Bolshoi Cherkassy Lane. By the way, that was where I first saw the People’s Commissar for Justice Nikolai Krylenko. I was stunned by his large, totally bald head, and also by his red eyes. It was only later that I realised he was systematically sleep-deprived as they were preparing all those political trials… Anyway, Grigoriev gave a lecture in the club, showing some of his famous pawn studies. They made an enormous impression on me, and that was the first time I sensed that chess wasn’t simply a game but was something more, that it was an art. And I also had the urge to master that field. That’s how I got involved in chess. My first success was a win in a simultaneous display against Alik Prorvich!

Back then I was still keen on volleyball. We had a very good gym and wonderful coaches. I was quite a decent volleyball player, a candidate for the Moscow team. Strange as it sounds, I wasn’t tall enough; I started to grow only when I’d already stopped playing volleyball. Just for curiosity’s sake I can tell you: when I started to play I was four centimetres short of the necessary height. In ninth grade my height was 1.69 m, but in the tenth – 1.82. I’d grown 13 centimetres in a year! I’d even faint at times as my heart couldn’t handle the strain. I grew until I was 25 years old, though in first grade I’d been the shortest in the class.

Yury Lvovich, you studied chess at the Young Pioneers Stadium, didn’t you?

I barely studied at the stadium and simply played there at a Category 3 tournament. My opponents were Tolush, Kotov and Chistyakov, while Linder took first place. Isaac is two years older than me. He was born in 1920 and back then he was undoubtedly stronger.

At one point the trainer at the Stadium was Yudovich, but then he moved to the Pioneers Palace. I also moved; besides, it was easier for me to get there. In order to reach the stadium I had to cross Arbat Street, get on a tram at Smolensk Square which ran along Garden Ring and then turned left to the Belorussky Rail Terminal. The journey took at least an hour. But just then they’d opened the first metro line, “the red branch” as it’s known today, and it became very convenient for me to travel to the Palace.

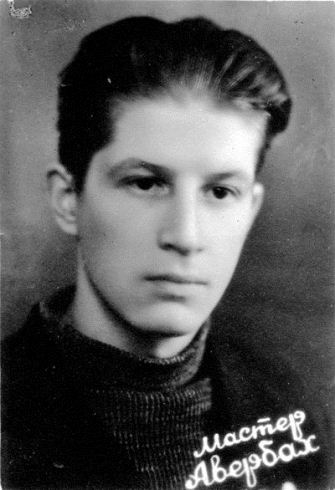

"Master Averbakh"

In team events I initially played on the third board for the Palace. I no longer remember who was first, but second was Vitya Khenkin. Then gradually I became the first. And when it was being decided in 1938 who should travel to the USSR School Championship they sent me. Everyone else there had Category 3, while I had the right to play in Category 2 tournaments. There was a story behind that. I was playing in a tournament with a Category 2 norm, I had 6.5/9, and suddenly it was decided that schoolchildren shouldn’t play against adults, and I didn’t finish that tournament. In order to get Category 2 you had to play a minimum of ten games. So they didn’t award me the category but just gave me the right to play in Category 2 tournaments, although I still couldn’t use that as there simply weren’t any Category 2 tournaments for children…

But thanks to that (I was the only schoolchild who had such a right) I travelled to the USSR Youth Championship, and on the basis of my results I was immediately awarded Category 1. So I’d actually jumped one step, immediately becoming a first-category player. At the time it was a great honour. I recall one of the first-category players saying: “Has it come to this? Guys like that (your humble servant) are getting the first category!” But a year later I took first place in the adult quarterfinals in Moscow. Then I finished first in the semifinal and immediately got into the final. True, I finished second from last, but the person who finished last was the one who’d made such unflattering comments about me.

And besides volleyball and chess it seems you also boxed?

I only boxed for a year; I can explain why. When collectivisation began in 1929 a huge number of children and adolescents immediately appeared in our yard because, to put it bluntly, the whole Moscow region rushed from the countryside to the city. In our yard there was a club which was turned into a dormitory for workers. It was a real rabble, where a cult of strength reigned. Therefore if you wanted to be equal in the yard you had to be able to give as good as you got. That’s why I took up boxing for a year.

How do you keep yourself in shape now?

In no way at all of late, unfortunately. I swam until very recently, having gone to the swimming pool from 1964 to 1996. The thing is, however, that they fitted a pacemaker and told me I mustn’t wave my arms around. And it’s also somehow become hard to get up early. Unfortunately, therefore, I still haven’t adapted. But I think I will adapt.

Do you continue to engage in social and educational activities?

I’ve always maintained relations with the Institute (and now Academy) of Physical Culture and given lectures there, while recently we established a chess faculty, strangely enough, in the Construction Institute. We’re also trying to make that into a chess centre. And we’ve also set up a scientific and technical library. The authorities were very sympathetic towards us.

Soviet players at the famous 1953 Candidates Tournament (from left to right): Tigran Petrosian, Alexander Kotov, Paul Keres, Yuri Averbakh and Efim Geller

The Anand-Gelfand World Championship match is taking place in May in Moscow. Are you going to follow it?

Yes, of course. Moreover, we’re planning to hold a seminar for historians in the library during the match, where we’re going to say something about chess history. The thing is that just now a great number of chess books are being published but, unfortunately, from the historical point of view they’re becoming worse and worse. For example, one book which was recently published by a serious publisher gives Dilaram’s mate, but Dilaram is unexpectedly transformed from a woman into a man! And there are plenty of such idiocies, unfortunately…

In general, I think history has its subtleties. First and foremost, all my experience tells me that in history two times two never equals four. It can be anything else whatsoever, but not four! And besides, history is written by the victors, and the defeated are always guilty. For example, we’ve all heard that Richard III was a hunchback and murderer. In actual fact, he wasn’t a hunchback. At the time there was a struggle for power between the House of Lancaster and the House of York. York won and, of course, they described all the events from their point of view. Another well-known story is of Mozart and Salieri. But Salieri didn’t poison Mozart! Moreover, Mozart’s children were taught by Salieri. However, as brilliant an artist as Pushkin pilloried the poor guy… [Pushkin’s “little tragedy” was popularised in the West by the film Amadeus – CiT]

Or here’s another interesting example from Russian history – Vladimir the Great. Why is he famous? For the Christianisation of Rus’. And his son, Yaroslav the Wise, is mainly famous for his daughter marrying the French king. But that out of the five children of Yaroslav the Wise all of the sons became kings while the daughters married kings – for some reason no-one knows about that. Why? Because in the Tale of Bygone Years, where Yaroslav and Vladimir are described, Vladimir is good – he converted Russia, while Yaroslav isn’t, because he relied on the Vikings and they had a great influence in Novgorod during his reign. So Yaroslav is very “bad”. But that’s not true at all. Yaroslav produced “Russian Truth”, one of the first legal works in Rus’. So the history of states is a history of a constant struggle for power. It was precisely such a battle that led to the invention of a game – chess. With its help people learned to fight and to defend.

Why did the Indians invent their game? Because in the first centuries AD a flood of savages from Central Asia rushed through the passes in the Hindu Kush to reach northern India. They had to learn how to fight off the attacks. The result was the emergence of chess. However, we still stick to the opinion that Central Asia was comparable in cultural terms with India. In actual fact, they were wild tribes who had only one idea – plunder and conquest.

Man didn’t immediately become a thinking being. First he was, in essence, an animal in human form. Do you know how Genghis Kahn fought? He placed his prisoners in front of his armies so people couldn’t fire at them. The times were different… Rus’ became an obstacle on the Mongols’ path; it came under the yoke but it saved Europe. I recall how at one point the Mongols wanted to hold very widespread celebrations for the anniversary of Genghis Kahn. A special decree was passed by the Central Committee of the Mongolian Communist Party about how great he was – he united the Mongolian tribes. But when the cattlemen united their pastures were no longer sufficient and they had to seize those of others… In general, people somehow managed to convince the Mongolians that the celebrations shouldn’t be held on quite such a large scale.

A historian shouldn’t be guided by the present day, but should try to take a very human look at things. In that way many events are perceived entirely differently. Do you understand?

Yuri Lvovich, did you ever discuss historical topics with Garry Kasparov?

I did, but I told him I didn’t support the New Chronology. I’ll explain why. Firstly, history isn’t arithmetic. History was written by monarchs; they relied on some source and tried to imitate the Greeks, or the Romans. It was no accident, after all, that Plutarch wrote Parallel Lives. He would take one Greek and one Roman and compare them. The monarchs would simply lie more in one place, or less in another, and you need to accept that calmly. The second point is that it’s one thing to recall what happened yesterday, but something else entirely when you recall what happened 50 years ago. Naturally you perceive things completely differently. In actual fact, Russian history contains an awful lot of lying, and that’s to put it mildly.

For example, the story about Ivan Susanin and the famous Life for a Tsar… Susanin was the tutor of Michael, who would be chosen as tsar only a year after the downfall of Susanin. Could a simple peasant have known about that, a year before Michael was put on the throne? Of course not. It was simply a normal human reaction not to want to allow the looting of his master’s estate. In the history textbook my mother learned from it was written that a band of either Poles or Cossacks was roaming the eastern part of Rus’ looking for landed estates to plunder. And Susanin led them away from that place. The “Life for a Tsar” that ensued is simply a lie. So that’s how it is. I think a historian should be sceptical. He should check something a hundred times before saying it.

I’d like once more to repeat my thought that overall the history of chess is very closely entwined with the history of the development of human thought. That’s what makes it interesting.

The world's oldest grandmaster with some younger players at Moscow's Central Chess Club

- Interview at the Russian Chess Federation website (in Russian)

Thank you for yet another wonderful translation! GM Averbakh still sounds perfectly lucid. Reminds me of my research adviser who gave a nice, sharp speech at his centennial celebration. I love the 1953 picture of a future World Champion and two perennial W.Ch. contenders. (Wishing Averbakh “Sto lat!”)

Having spent over 8 weeks in central Moscow last summer I was rather familiar with the streets and intersections mentioned by GM Averbakh throughout the article. I very much enjoy reading his insight on chess history and in the history of other board games.

Superb interview and translation! Appears that Grandmaster Averbakh mind is as sharp as ever! Great article!

I’m glad someone got something out of the street names! That was probably the most time-consuming part of the whole translation :)

An article worth to read at least a second time!

A very interesting article on history of chess.The origin of chess has been debated endlessly. This adds another dimension to the whole debate. One aspect that was touched here superficially was the Iranian connection.

Is it possible that the iranians imported the game from India? They were involved in trade with India for a long time:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shatranj

The term shatranj itself could be a derivative of the Indian term chaturanga. Would it also be possible that the kings played the game to pass time or strategize against each other, rather than fighting the central asian army?

I hope my brain is half as sharp at 60 as his is at 90!

Wonderful of an article! So wise, so analytical views by Mr. Averbakh – On maectro na vce ryki!

This is a wonderful and thought-provoking interview. It’s great to hear any form of critique of chess literature,especially when it coems from within the game itself.

Thank you for the translation, highly enjoyable.