Giri at Tata Steel Chess 2012 | photo: Fred Lucas

Anish Giri is currently the world’s most promising junior, but although he now represents the Netherlands he started his chess career in St. Petersburg, Russia. One of his first coaches, Asya Kovalyova, explains how a chess superpower let a prodigy slip through its grasp.

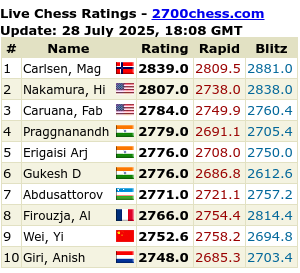

Although still only 17, Anish Giri has already won his first super-tournament and is a fixture in the list of 2700+ rated grandmasters. His only competition for the title of most-talented junior comes from Fabiano Caruana, who is nevertheless two years older. Giri is the son of a Nepalese father and Russian mother and grew up in St. Petersburg, where he was born on 28 June 1994. In 2002 his father took a job in Japan, with Giri eventually following him there, although the family would still regularly return to Russia. In 2008 they moved again, this time to the Netherlands, and Giri soon switched chess federations. Nevertheless, the language Giri speaks at home is Russian, and his first success in chess came in Russia.

Asya Kovalyova is a chess coach at Sports School No. 2 in the Kalininsky District of St. Petersburg (for more information see the Wikipedia article on the Soviet system of sports schools, and the school’s Russian homepage). In an interview with Sergei Lopatenok for www.online812.ru she describes her first impressions of Anish Giri and how a lack of money delayed his claiming the IM title.

How did Anish Giri end up at your school?

He came to us as a first-grader. He was brought along by a boy who lived in the same yard. That kid was talented, but a funny thing happened: he gave up chess when Anish started to do better than him. His grandmother just couldn’t understand how Anish had only just come along but was already beating her grandson, and she stopped bringing her grandson to the classes.

Did you recognise Anish’s talent quickly?

In the initial stages classes are held in groups, and of course you immediately pay attention to a kid if he raises his hand and is ready to answer your questions. In a couple of months it became clear the kid was talented, and in something like half a year I realised he wasn’t simply talented. He also had an extremely high intelligence. At one tournament Anish was given Karpov’s book “My Best Games: 100 Wins in 30 Years”, and a couple of days later he’d read the whole of it, although after all it wasn’t a work of fiction but an analysis of games. It was as if he’d photographed them and knew them by heart. An intellect of the very highest level.

Is that down to his parents or something he was born with?

It’s God-given. It’s something you can’t develop and you can only get with your genes. He was born like that.

Did his parents play chess?

His dad didn’t, I think, while his mum played, but the way everyone knows how to play in Russia, at an amateur level. Essentially she simply knew how the pieces move. But the parents supported their son’s interest, and that was their main task in the early stages.

The family lived in Japan for a certain length of time. In terms of chess was that time lost for the boy?

You could say that. First his father went, then his mum, for a while the boy stayed here with his grandmother, but then he also went. You could say he didn’t study for a year and a half. He tried to do something over the internet, but that’s not serious if you’re talking about professional training. There was a period when Anish needed to be kept in chess and inspired, and I think us coaches (Andrei Praslov also worked with him) can take some of the credit for saving him for chess.

What level did you get him to?

When he left us he had an IM rating. In order to complete the relevant paperwork we needed to pay FIDE – to transfer 17,000 roubles to Switzerland. [In 2007-8 that would have been about 700 USD – CiT] The director of our school took that upon himself. In a meeting with Chazov, at the time the head of the Sports Committee, he said we had a talented kid but couldn’t pay the fee and asked for help. Chazov wrote to the chess federation, although that’s a national organisation while we’re a municipal school. As often happens, the federation had its own problems at the time. It’s remarkable that the city didn’t manage to find 17,000 roubles. Chazov could, of course, have found it.

But couldn’t his parents have paid that 17,000 roubles?

The family was having a tough time financially – thousands of roubles was a lot of money for them. They had three children, after all. There were grants from the All-Russian Federation, but Anish didn’t get one. Perhaps they were more interested in Muscovites and had individuals they were promoting, but they didn’t help someone who really needed it. Then as soon as the family ended up in Holland the boy was immediately targeted. He moved in February, played his first tournament in April and then again and again, and in December he had a grandmaster norm. You need to invest in talent. They did everything for him there despite his having a Russian passport. He turned out to be in demand and plays exclusively in super-tournaments. Here, on the other hand, I heard a radio interview with Glukhovsky, the editor of the “64” chess magazine. He was talking about Giri and made it sound as though we’d failed to spot him in Russia. But how can you say we failed to spot him if we sent letters to Moscow to coaches who deal with juniors asking them to pay attention to our guy.

Giri with his sisters and Sopiko Guramishvili celebrating New Year 2012 in Reggio Emilia | photo: Martha Fierro, Accademia Internazionale di Scacchi

Do you have any contact with Anish and his family now?

We regularly exchange greetings, and I talk to his grandmother.

After becoming famous many sportsmen give their coaches flats and cars. Has it reached that stage for you?

There isn’t such crazy money in chess as in tennis or football. When you reach the level of World Championship matches then it’s a different matter.

And does a chess coach at a children’s sporting school earn as little as a school teacher?

It’s possibly a little better for us on account of a greater number of hours.

Do children still come to study chess?

The parents bring them. Of course in the USSR chess was treated with much greater respect and now children have far more options for expressing themselves and keeping themselves busy. But nevertheless, people still play chess, although it’s extremely rare to encounter a pupil like Anish.

Ilyumzhinov introduced chess as an obligatory school subject in Kalmykia. Have there been any such attempts in St. Petersburg?

A couple of schools have experimented, but that only lasted as long as they received support from the chess federation – above all, financial support. When that ended, and it became something the headmasters didn’t need, everything was shut down, although in the Kirov District there’s still one school that’s working on that.

- Interview at www.online812.ru (in Russian)

I can now better understand why you do not want to translate more articles. Your publications are like a “kiss of death”. Not only Bartel, but now look what’s happening to Giri in Plovdiv.

But seriously, I hope that what’s happening to Giri is just a normal teenager trouble. But it’s funny to see, past the midpoint of a serious tournament, a 2717 GM have the same number of points (3) as a 2027 FM. Might I (closer to 1200 than to 2027) have a chance with Giri now?

Bartel is doing relatively OK in Plovdiv, he just quit rising for the moment. And overall it isn’t mishanp’s fault, he didn’t write anything recently about Mamedyarov and Navara! :)

Yep, I knew the “rise and rise” title was asking for trouble! At least Bartel’s only lost 7 points or so at the moment – he’s got a risky style and must be exhausted after all the tournaments he’s played in a row. I refuse to take all the blame, but I might well publish something about Navara in the near future :)