Boris Spassky, the Tenth World Chess Champion, today turned 75. In a long interview he talked about his introduction to chess, the road to the title and his friendship and rivalry with Bobby Fischer, as well as about his personal life, from surviving the Siege of Leningrad to his first unsuccessful marriage and moving to France.

Boris Spassky, the Tenth World Chess Champion, today turned 75. In a long interview he talked about his introduction to chess, the road to the title and his friendship and rivalry with Bobby Fischer, as well as about his personal life, from surviving the Siege of Leningrad to his first unsuccessful marriage and moving to France.

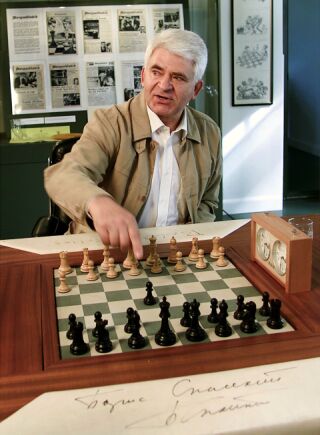

Kirill Zangalis states that the interview, published today by the Soviet Sport newspaper, was actually conducted by him in Moscow in September 2010, shortly before Spassky suffered a stroke. The grandmaster’s recovery meant the text of the interview, which took place outdoors in warm autumn weather, was only approved in recent days. The photos, unless indicated, are taken from the “Congratulations to Boris Spassky on his 75th Anniversary” at the FIDE website.

I don’t like Moscow. It’s a difficult city. What linked me to it was the “Chess Week” newspaper. That was intended for the provinces and children and had a circulation of around 20,000 copies. I was the editor-in-chief for one and a half years. It suffered from a lack of money and at some point everything fell apart. And now I mainly only come to the capital on business…

You correctly noted that the best times for chess are behind us. I think the golden age came to an end somewhere in the late 1960s, which corresponded to the peak of my career. At the time everyone knew Botvinnik, Smyslov, Keres, Tal, Petrosian, Bronstein, Geller, Korchnoi, Stein, Polugaevsky and a few others.

Spassky - Larsen at the USSR vs. World match in 1970 | photo: ChessBase

In 1970 the so-called Match of the Century took place in Belgrade: the USSR team vs. the Rest of the World. All the great grandmasters were present at that match. We should have been at least about six points better, but we almost lost. Our team wasn’t unified team because the board order was decided by the USSR Sports Committee. I decided not to engage in an argument with such authority – I recalled the history of the powerful Persian King Darius III, who once, on surveying his 100,000-man army complete with powerful battle elephants, each of which in contemporary terms would be equivalent to an intercontinental missile, wept.

“What’s wrong, your highness?” someone close to him asked.

“I was imagining that in a few decades nothing will remain of this power. My soldiers and I will all have grown old.”I experienced something like that myself, as the leader of the Soviet chess armada.

Boris Vasilievich, is it true that you almost died from hunger in an orphanage?

That happened too. In the summer of 1941 I was evacuated from the besieged Leningrad with my older brother Georgy, to the village of Korshik. That’s 50 kilometres from Vyatka. We were incredibly lucky as we slipped out in the second group: the first and third were bombed.

Your parents died?

No, miraculously they survived. My dad was a soldier. My mum buried my grandmother and survived only because she inherited her ration card. My father was on the verge of death from starvation and even ended up on the death ward. You’ll never guess how my mother saved my dad: she sold all her things and bought a bottle of alcohol. She arrived in the ward and started to look for him among dozens of people, but he’d lost so much weight that she didn’t even recognise him. My father was stern despite his weakness and shouted at her: don’t you recognise your own husband? After that he drank the whole bottle and got up. A miracle? No, they say vodka has calories. The moment my father recovered they immediately travelled to our orphanage, when I was dying from hunger. My parents took my brother and me to the outskirts of Moscow where we lived until the summer of 1946.

How did you learn to play chess?

In the orphanage I learned the rules of the game while watching the older children playing. One evening, when there was no-one there, I took away an outside pawn and used the rook to eat up the whole white army.

In 1946 you returned with your family to your native Leningrad…

Yes, and a couple of months later I was in thrall to chess. Once, on the Kirov Islands in the Central Park of Culture and Rest, I accidentally came across a glass-enclosed veranda, which had a black knight on the front. It was a sunny day and the wind was rustling the leaves of the birch trees. It seemed as though there was nothing particular to catch the imagination of a child, but I saw a fairy-tale world. And it captivated me. Behind the glass there were tables, on the tables were boards, and on the boards were pieces. I lost my sense of reality. Each morning I’d rush to the park.

You were only on the chess throne for three years, or one cycle…

You can’t imagine what a relief it was when I ceased to be World Champion. Those were the very toughest years of my life, when responsibility pressed on me and I didn’t get any outside help. I was the king and I had to answer for every word.

The moment I became the Champion my trainer, the Don Cossack Bondarevsky, told me: “Now you can arrange your own life: enter the party, become the editor-in-chief of “64” (Petrosian was the editor), travel to the Damansky Peninsula and take up some social activity. “No, vater, that’s not for me”. “Well, you’ll see for yourself”. (I called my trainer “vater”.)

You made it into the Candidates very early on, buy you only won your match in 1969.

Yes, at age 19 in 1956 I played in the Candidates Tournament. It was obvious that sooner or later I’d become World Champion, but it was sooner said than done. “You’ll suffer from girls”, said my trainer Alexander Kazimirovich Tolush. And he was right. The first time I got married was early on, at 22. Almost immediately I realised that my wife and I were opposite-coloured bishops. Military actions commenced. I ended up in hospital because of nerves. I was saved by Mikhail Yurevich Cherkes, the manager of the Moscow railway. He provided me with a one-bedroom flat while my militant wife moved into my socialist mansion. That was how we split up, and it was the green light for the chess throne.

When did you sense it was time to storm the heights?

It was in 1963 at the match between the teams of Hungary and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in Ordzonikidze. At the time I told my trainer: “Vater, perhaps I should become World Champion?” – “Ok, let’s do it!”. That was how our work began. I remember all my trainers with great reverence and respect. Vladimir Zak gave me a weapon, Alexander Tolush sharpened it, Bondarevsky hardened it. With that weapon I became World Champion. But that took six years of fierce struggle against Petrosian.

People say you weren’t particularly hard-working?

I played my systems and didn’t particular like to learn new ones. I relied on my skill in the middlegame. By the way, it was the same for Capablanca. Overall, of course, I knew the openings badly, but in my own systems I felt confident.

But after all without openings you can’t make progress, it’s the ABC of chess!

That’s nowadays. At the time I quickly got my bearings in any position. I’d find a plan and my main strength was that I had a good feel for the critical moment. If you’ve got that talent you have the ability to find the only correct path in a critical position. By that I mean not only an individual move, but a whole concept based on calculation and an evaluation of the variations you’ve analysed. That’s a talent that even the World Champions haven’t always possessed.

So why didn’t you manage to overhaul the iron Tigran Petrosian in the first match?

I came into the match against Tigran Petrosian completely exhausted after getting through 98 difficult qualifying games. During the final stages there were bloody matches against Keres, Geller and Tal. The most difficult match was against Keres, which turned into a street brawl. Geller was relatively weak in defence and I only needed to attack him at all costs. I didn’t allow Tal to seize the initiative. That approach brought me success. However, in order to beat Petrosian I needed something new. It’s very important to be imbued with a sense of the inevitability of your own victory. Your opponent senses that. But for that you need to have spirit and matter in harmony. In my case I was a poor student, unsettled and very far from higher thoughts. In the first match I flung myself at Petrosian like a kitten at a tiger, and it was easy for him to parry my blows. But by the second I’d matured and turned into a bear that was always putting the tiger under pressure, by which I mean I held him in a grip that even if it was loose was constant, and he didn’t like that.

How did you manage to withstand such pressure?

I restored my strength through sleep. Sometimes I’d sleep for ten hours a day. Of course, it also helped that I did sport. In my student years I did the high jump – my usual result was 175 cm. Later tennis became my faithful assistant.

Could Petrosian have held on in the second match?

It seemed to me that Petrosian was mentally tired of being the Champion. After all, he held the crown for six years without being the strongest player. That was evident from his tournament results. Perhaps that had a certain effect on him.

Finally, a quick story. After the 17th game (I think that was the decisive one) there was a terrible knocking on the door of my Khrushchev-era flat, and then an unknown voice with an accent said: “Listen, Boris, don’t you dare beat our Tigran!” “I’ll be sure to beat him”. Strangely enough, my reply calmed the rabid fan down.

There are legends about your relationship with the World Champion Robert Fischer.

I was friends with Bobby. He was an unusual man. I saw him for the first time in 1958, when he was 14, and liked him immediately. I got to know him better in 1960 at the tournament in Mar del Plata. Fischer was an absolutely unsocial man, an alien.

During the match in 1972 you were enemies?

Of course, but only during the struggle. We always had great respect for each other.

You won the first game easily, but Fischer made a point of not appearing for the second. You could have retained your title and left.

I could. And I was advised to do that. I’ve even heard criticism that I played that match for money. As World Champion I considered I was obliged to play the match. I had to play and there was no point in thinking about anything else. Victory brought me inner balance. The loss – clarity and financial compensation.

Why did Fischer win?

From a chess point of view Fischer was already stronger than me. His time had come. But in that particular match he put himself in quite a tough psychological situation. His conflict with the producers, his haggling with the Icelandic organisers to get paid box-office receipts, his fear of sitting at the board as after all up until that moment Bobby hadn’t won a single game against me and I was leading with a 4:0 score – all of that left him in a state of extreme uncertainty. But nevertheless, at the decisive moment, when the third game was supposed to take place, I made a serious psychological error: during an argument with the chief arbiter for the match, Grandmaster Schmid, Bobby behaved quite badly. I should have made a show of getting up and refusing to play – I’d have resigned that game and got a zero, but at the same time I’d have preserved my nerves. In that case Bobby would have got an empty point and nothing more, and my moral conviction would have grown.

What were the special features of Fischer’s chess?

Strict logic and a computer-like approach.

How can you be friends with such a strange person?

Easily. For example, he couldn’t stand it when people phoned him, but I never bothered him. He always called me himself. Only on one occasion did I write him a letter. I was already living in France and had no money. At all. I needed work. I was invited to work on the Karpov – Korchnoi match in 1975 as a commentator. I asked Robert for advice. His reply was as follows: “Boris, whatever those people offer you, no matter what dirty money they promise you, never have anything to do with them. You’re an honourable man.” I listened to Fischer and turned them down.

Did you meet often?

Yes. Once we had a rendezvous in an empty restaurant. Robert, who had a persecution complex, rushed to search the premises. He was always looking for spies. I calmed him down: “Everything’s ok, Bobby. I’ve already destroyed all the Soviet surveillance cameras”.

Have you visited his grave?

Yes. I paid my respects at it in Reykjavik.

In 1976, after marrying your third wife, a French woman with Russian roots, you left the USSR.

Yes, I never hid the fact I wanted freedom. I dreamt of calmly playing those tournaments I was invited to. And Marina Stcherbatcheff gave me that option. For a long time they didn’t want to allow us, as after all back then marriages between socialists and capitalists were forbidden. But thanks are due to Leonid Brezhnev. At least he did one good deed. Marina appealed personally to the French President Georges Pompidou, and he managed to persuade Brezhnev.

A story like that of Vladimir Vysotsky and Marina Vlady…

I wouldn’t compare it. The whole world followed the romance between Vysotsky and Vlady. It was a little different with us.

Where do you feel at home?

In France. It’s a good stepmother. Russia’s a sick mother.

But you’ve started to come here regularly.

I do a lot of work in Russia. I opened a school in Satka, where I teach little kids.

Do your children play chess?

No. Boris Junior, who’s now working in Tajikistan in the cotton business, once asked me to introduce him to the game. However, when he made the moves h3 and Rh2 for White I realised it was something he simply didn’t need.

Are you a happy person?

I’ve lived a good life.

Can you allow yourself not to work?

No, I need to feed my family.

There’s no prize money left?

You want to hear a story about prize money? In 1972 after losing to Fischer I got my hands on around 93,000 dollars.

A fortune for those times!

I’d lost it all four years later!

That’s impossible!

It turned out it was possible. Do you recall “Mimino”: “Vakh, what kind of person comes to Moscow without money? They went out on the town, drank it all”…

In the second showcase match against Fischer in 1992 the two of you received an unheard of fee of five million dollars. What happened to that money?

I bought my family and friends eight flats. Why did I need so much money? As long as I was fed and clothed. I’m a man of few needs.

Am i glad to see you back !

Thank you for the wonderful translation and for bringing my favorite chess site back to life!

Great to see this site running again!

What a nice interview! Spassky should have written an autobiography.

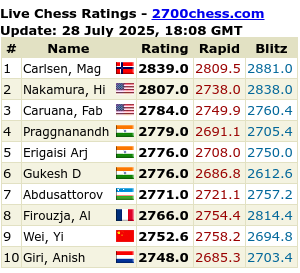

Interesting when he compared himself with Capablanca in not caring much about openings and winning the middle-game. He must like Carlsen a lot on the same basis!

Reading the interview is just like meeting an old friend whom I haven’t seen for 20 years.

I did meet spassky 25 years ago. he was a very nice man.