Vitaly Tseshkovsky, who died on the 24th December, coached the young Kramnik in the years when he broke into the World Top 10. Kramnik has now shared his recollections of Tseshkovsky, noting his talent was comparable to Timman’s, but he lacked the sporting and political skills required to top world chess in that era.

Vitaly Tseshkovsky, who died on the 24th December, coached the young Kramnik in the years when he broke into the World Top 10. Kramnik has now shared his recollections of Tseshkovsky, noting his talent was comparable to Timman’s, but he lacked the sporting and political skills required to top world chess in that era.

First published but no longer available at WhyChess – more here

The following is a full translation of Kramnik’s Russian text at the Russian Chess Federation website:

I’d heard, of course, that Vitaly Valeryevich’s health was no longer so great, but such things always come as a shock… After all, he was only 67, which isn’t such an advanced old age nowadays.

We hadn’t seen each other for a long time as our paths somehow never crossed – I’d play in some tournaments while he played in others; but we always had a good relationship. Of course, when I saw the sad news on the internet memories immediately flooded back…

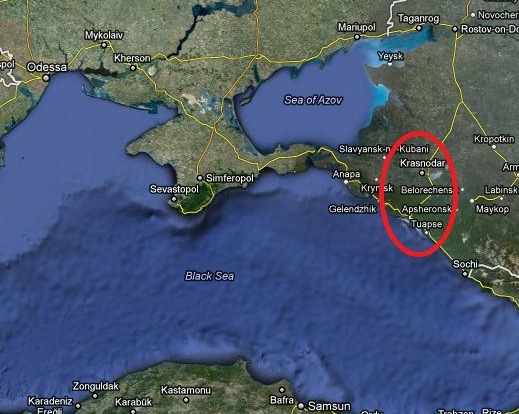

We worked together very closely from 88-89 to 94. We were neighbours: I was living back then in Tuapse while Tseshkovsky was in Krasnodar. From time to time someone would work with me – one local master or another. At some point it became clear that I could develop into a very strong player, so they decided to find me a coach who had a very deep understanding of chess. Tseshkovsky automatically emerged as a candidate – in the Krasnodar Region there were no other chess players at his level.

Kramnik was born in Tuapse on the Black Sea coast, about 150 km from the regional centre of Krasnodar

The only problem was that Tuapse and Krasnodar weren’t located very close to each other, so it wasn’t that easy for us to meet often. Moreover, he was still playing regularly himself, and posting very decent results. So we spent more time together at tournaments, and sometimes at training camps. On more than one occasion we stayed in the same hotel room when he was helping me at junior competitions. Of course we talked and worked a lot on chess. Back then I was still very young, so we didn’t quite communicate as equals. He certainly didn’t treat me as a child – he shared his thoughts with me and told me a lot of interesting things – but there weren’t any disputes or long dialogues between us, as after all we were people from different generations. He was a very intelligent, scrupulous man and never applied pressure or imposed his opinion on me. He’d apologise five times before expressing his disagreement with something. He was an honest, decent man, and had no malice at all. He might not get on with someone very well, but I never heard malice in his voice. He had no desire to settle scores with anyone or take revenge and so on. It seems to me he never did anything bad to anyone.

Tseshkovsky was a very interesting, original and unconventional chess player. Above all, he really loved chess. He was one of those rare people who could analyse any position. I remember his favourite pose: half-lying on the bed, supporting his head in his hands; in front of him – a magnetic chess set from Riga, which he always took with him. At junior championships when I returned to the room I could find him, for example, analysing some game from the “64” magazine; let’s say, Rodriguez – Gutierrez from the Columbian Championship. If a position caught his interest he could analyse it for three or four hours. He moved the pieces, had a think, moved the pieces, and again had a think… That seemed a little strange to me and I once said: if you like analysing so much perhaps it would be better to take some position from your repertoire? But he was ready to study any idea that caught his interest. That, of course, is a rare quality, found only among people who genuinely love chess!

It seems to me that Vitaly Tseshkovsky didn’t achieve all he could because he loved chess too much: he had an enormous love of playing and analysing, while the practical result didn’t particularly bother him. Of course, he had to earn money and take care of his family, but essentially he simply loved playing chess. I’ve rarely met such enthusiasm for analysis! He could be drawn into some study or even a selfmate. He’d put it on the board and spend half a day solving it. I was amused by all that, and us kids would laugh at him when he’d enthusiastically tell us: “A difficult puzzle, but how interesting!” There’d be some irrational position on the board – a selfmate in 10 moves or some such madness! And he’d share his emotions: “I already have a sense of what the construction should be, but I just can’t grasp the correct path…” It was a unique spectacle, and there are less and less such people…

Whether Tseshkovsky was at the same level as the great or a little below them is something I won’t try to judge; in general, it’s very hard to judge the scale of anyone’s talent. But it’s obvious that his sporting qualities were zero. He “got by” on account of his love of chess and his talent. If only he could have added sporting qualities… When he was on fire he would rip everyone apart, and no-one understood what was happening on the board! He had an amazing style: he really loved complex positions, and would deliberately complicate, complicate and complicate play… Moreover, by complex positions I don’t mean simply that they were tactical; he loved it when a lot of pieces remained and when, as far as possible, the struggle was taking place across the whole board. He loved to provoke turmoil on the board, when it was difficult to grasp what on earth was going on. That was his element, in which he’d outplay very strong grandmasters, and at times outplay them as if they were mere children. Of course he also had weaker sides to his game, but overall his style was very original and unconventional; I don’t even know who you could compare Tseshkovsky to. He always approached a position without any clear criteria for evaluating it: this is better, this is worse. He “diluted” me in this sense: after all, I’d studied the books of Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch, and the criteria there are very strict – this is good, this is bad. Vitaly Valeryevich, of course, understood chess more deeply than I did at the time and he was able to demonstrate that chess is much more multifaceted and not so categorical; sometimes it’s hard to grasp in general whether a position’s better or not. He enriched me in that regard.

I remember either in 1990 or 91 that we were at a training camp in Novogorsk before the World Junior Championship. The camp lasted a long time, about a fortnight, and it was boring to study all the time. At some point we sat down at the board and I said, “Perhaps we can play a little blitz?” He said: “Come on, then!” I was about 15 or 16 years old at the time and I was already playing pretty well. Of course, he was a stronger chess player, but I was young and my mind worked very quickly. Like any young chess player I loved to play blitz, especially against such a great player. He also really enjoyed it. And so we wound up playing for three days in a row, only taking a break for food and sleep. We didn’t even take any walks!

At first we kept a score, then we stopped, but it was about even: over three days perhaps someone won with a maximum of +5, while we played more games than you could count! No-one was particularly bothered about the score as we were both so caught up in the game, but for the sake of interest from some point we started to divide our marathon into 10-game matches. Sometimes I’d win a match, sometimes he would, but the gap was always only 1-2 points, no more.

Vitaly Valeryevich undoubtedly had a serious influence on my development as a chess player. As a youngster it’s very important to spend time with a strong player. I wouldn’t say that we analysed a great deal, although that also took place, but if you’ve got the ability to learn then it’s very important to have contact with a major player who sees the game differently and simply understands chess better than you do. He didn’t prepare special topics for our work together, but we’d simply sit at the board and start to look at certain positions, more or less related to my repertoire, though at times with no relation whatsoever. Sometimes he’d simply say: “I played an interesting game. Let’s analyse it!” And we could spend a few hours investigating that game. Of course, such an analytical process really enriched me. Tseshkovsky shared his thoughts, ideas and conceptions, and that was very useful.

In about 94 our cooperation came to an end because at that point chess had started to change significantly. Computers had appeared, while Vitaly Valeryevich worked the same way he always had, and wasn’t quite able to keep up with the growing volume of information. He analysed at incredible depth, but very slowly. That’s perfectly natural, but I had the impression that I simply wouldn’t have the time to process the necessary volume of information; it was better to sacrifice a little depth but look at more. I started to try working with different, younger people, who knew how to handle computers. Vitaly Valeryevich and I had no personal problems, but in terms of cooperating our paths gradually began to diverge. He was a man from a different generation, and it was hard for him to adapt to start working with computers. He loved chess more as a game than a profession. I was already in the Top 10, and I had “to work my socks off”, regardless of whether I liked positions or not. For example, a slightly worse endgame had to be brought to a clear draw. Vitaly Valeryevich, on the other hand, wasn’t mentally prepared for such work. He loved chess as creativity. I understand that perfectly and welcome it, but back then that was already insufficient in order to reach the top. Our paths diverged, although afterwards we would still sometimes see each other and talk. In any case, our cooperation was very useful for me.

Of course it’s sad that people are leaving us from the generation I was connected to in my childhood. Recently Igor Yulyevich Botvinnik passed away, and I was also very upset when I saw that news during the tournament in London. I didn’t expect it at all as he’d always been so optimistic and had never complained about anything… Frankly speaking, I didn’t even know that he was over sixty; it always seemed to me that he was quite young. Literally a year ago we met in Paris, where he’d come to visit with his family. We met, had a good time together, and everything was so cheerful…. When I was accepted into the Botvinnik School he’d handled all the technical details and was a very good-natured man. Such blows one after another, people passing away. It’s a great pity, as you lose a part of your past…

Igor Botvinnik, Mikhail Botvinnik’s nephew, passed away at the age of 61 on 5 December, 2011 | photo: RCF website

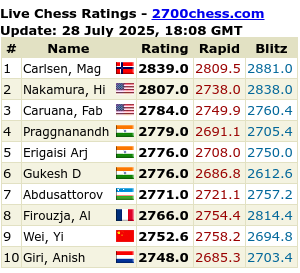

There are very few people left who are as selflessly devoted to chess as Vitaly Valeryevich was. He was a very independent, proud man, who didn’t like any kind of pressure, and was absolutely incapable of any bootlicking – that was incompatible with his personality. That was probably why Tseshkovsky was very rarely allowed to play in overseas tournaments, as at the time you often needed to “grease palms”, to smile at someone at the right moment, bring them a little present and so on. But he didn’t like any of that, so he rarely travelled. In that sense he was a man from a “lost generation”. I think if he’d gone abroad, like Korchnoi, he’d have become a major player, at Timman’s level – he’d have been a constant in the Top-10. Although it’s hard to imagine Tseshkovsky living abroad as he was so Russian, so connected to Russian culture. At home he soured a little: he had the talent, but no tournaments. He told me that at some point he lost interest in his chess career development. He realised that he wasn’t Karpov, he wasn’t so great that they’d give him all the tournaments, but on the other hand while he didn’t have the tournaments he had no chance of becoming great. Tseshkovsky said: “I’m not capable of behaving so that I beg for these tournaments”. In a certain sense he gave up and decided that he’d simply play chess for pleasure.

Of course, there are lots of funny stories about him. There was one he loved to tell himself. Tseshkovsky was offered the chance to move from Omsk to Krasnodar so that the region would have its own very strong chess player. They gave him a big flat in the centre of the town on Krasnaya Street and offered good financial conditions, which immediately made him an eligible bachelor. And then he had a very serious romance and he and his beloved were already thinking about marriage. But – things just wouldn’t go well with his potential mother-in-law. It seemed as though she also wanted her daughter to marry a famous chess player, but nevertheless she had a dislike of Tseshkovsky. Now I’ll try to reproduce how Vitaly Valeryevich would tell it:

“One fine day I was standing at the bus stop, waiting for a bus and smoking. At that moment my future mother-in-law passed by and after brief greetings she uttered the following phrase:

– So, Vitaly, it turns out you also smoke!

After that I couldn’t restrain myself and replied:

– I also drink and love chasing after women!

And with that the romance suddenly came to an end.”

Tseshkovsky was a very direct man, with a sense of his own dignity. He could tell the chess leadership things to their faces. He was highly respected, but other people who were, let’s say, more tractable, would be sent to tournaments. It’s a pity that he didn’t achieve all that he could have done in chess. And in general, he could have lived longer. It seems to me that nature had granted him colossal – genuinely Siberian – health.

In his case it’s very symbolic that he died at the chessboard. After all, he played to the end – simply because he loved to play. I don’t think it brought Tseshkovsky much money, and any straightforward coaching activity would have earned him no less.

Farewell, Vitaly Valeryevich! May you rest in peace.

Original at the RCF website (in Russian)